He couldn’t see ten feet in front of him.

That’s what we always say down here in the South when someone’s vision is impaired.

In this case, I’m not sure exactly how far he could see but I suspect it can’t be measured by feet.

The Bible says, “Do not withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in your power to do it.” That’s Proverbs 3:27.

It’s rarely in my power to do anyone any good at all as far as I can tell, but some years ago I had a recurring opportunity, and I took it whether I needed to or not.

A man I knew—not as much as I know some people or as little as I know others—was nearly blind, at least as far as driving was concerned, and he and I both knew it well.

For the sake of this story, I’m going to call him Shorty.

I’m really calling him that because it was his name, and nothing else would fit him anyway.

I can’t say what Shorty was like his whole life, although as circumstances would have it, I know more now than I did then and we’ll get to that later.

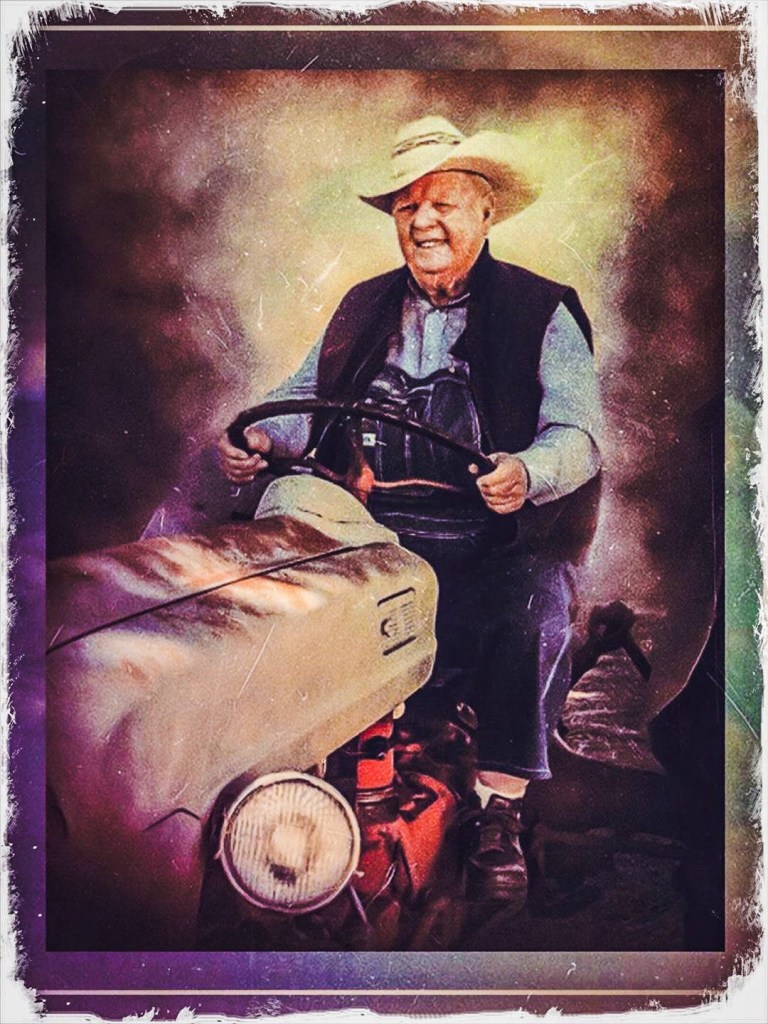

Mostly what I knew about Shorty at the time was that he had a grin to split his whole face when he walked in to see me, and he drove his tractor and no other vehicle.

You don’t need a driver’s license to drive a tractor.

However, for a lot of older people a license is a symbol of their independence and this causes them to cling fiercely to it, heartbroken and defeated when forced to give it up, even though they have zero intention of driving anywhere.

If you haven’t guessed by now, I worked for the place where those exact things were issued up until my retirement last year.

Shorty had already been gone a few years when I retired. I believe he was 92 when Jesus called him to plow the south forty in Heaven. Something close to that.

He had a particular way of walking, and as far as I could tell, he always wore a pair of overalls.

Everybody around here knew him and everybody loved him. He was that kind of man. I’ve learned since those days he could be quite grouchy, but I didn’t see that side of him.

Shorty owned the oldest building in the town he lived in. I’m calling it New Llano, mainly because that’s the name of it.

From the information I got off the internet, New Llano was originally started by a bunch of pre-hippies from California in 1914 as some sort of socialist commune, but it only lasted a few years like that and was made into a colony by the people who didn’t vacate the premises.

The building Shorty owned was the General Merchandise store for the colony.

He was quite a collector, and with his wife ran an auction out of that building. Shorty also sold antiques and farm equipment to people who stopped in, but he wasn’t above cussing and chasing them off his property if they didn’t want to pay the price he set.

He didn’t care how long something sat in his building, eventually someone would come along looking for that very thing and be willing to pay his price for it. Or it would just sit there collecting dust forever because he was a wonderful, stubborn old fella and it didn’t matter to him if anyone bought it or not, by God.

Shorty always carried a huge wad of cash in his pocket.

I saw it myself several times, and now it’s been explained to me that he kept it on him so he could offer a cash price for something he saw that he might want and he didn’t mind taking a walk if they didn’t take it. Someone else would.

He and his wife lived in a mobile home behind the auction house, which is just over the train track.

The story is that if a train conductor came through and blew the horn a couple of times and moved on, Shorty only had good things to say. But if the guys who laid on the horn would’ve been able to see Shorty and hear what he had to say to them, their lives might never be the same.

Shorty was a little guy with the biggest smile that lit up a whole room.

He could make me laugh and I feel like he genuinely liked me, and you don’t always feel that way with people. I know he loved his family with his whole heart.

In the end, Shorty forgot most things and a lot of people.

92 years is a long time to try to keep remembering anyway. He kept the older things better, like knot tying from his navy days.

Thinking you’re young again can’t be the worst thing there is.

I wouldn’t have been able to bear the hurt in old Mr. Shorty’s eyes if I had taken his license from him, although it was easily in my power to do it. Instead, I renewed them every four years just like he could see ten years in the future.

Which is ironic really.

Because here we are, about that far down the road, and a month ago I married Shorty’s son.

Every time I watch my husband walk across the yard I see a particular walk and I think about Shorty, and how he drove his tractor.

And if I had it to do again, I would.